Reading--Notes

Local Storage

In the beginning, there was only Internet Explorer. Or at least, that’s what Microsoft wanted the world to think. To that end, as part of the First Great Browser Wars, Microsoft invented a great many things and included them in their browser-to-end-all-browser-wars, Internet Explorer. One of these things was called DHTML Behaviors, and one of these behaviors was called userData.

-

In 2002, Adobe introduced a feature in Flash 6 that gained the unfortunate and misleading name of “Flash cookies.” Within the Flash environment, the feature is properly known as Local Shared Objects. Briefly, it allows Flash objects to store up to 100 KB of data per domain.

-

In 2007, Google launched Gears, an open source browser plugin aimed at providing additional capabilities in browsers. (We’ve previously discussed Gears in the context of providing a geolocation API in Internet Explorer.) Gears provides an API to an embedded SQL database based on SQLite. After obtaining permission from the user once, Gears can store unlimited amounts of data per domain in SQL database tables.

INTRODUCING HTML5 STORAGE

What I will refer to as “HTML5 Storage” is a specification named Web Storage, which was at one time part of the HTML5 specification proper, but was split out into its own specification for uninteresting political reasons. Certain browser vendors also refer to it as “Local Storage” or “DOM Storage.”

what is HTML5 Storage?

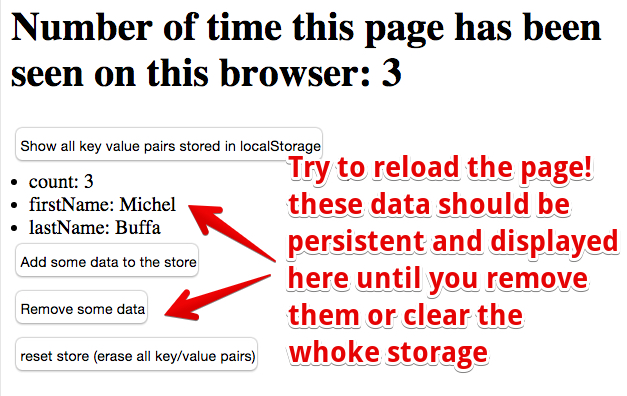

it’s a way for web pages to store named key/value pairs locally, within the client web browser.

TRACKING CHANGES TO THE HTML5 STORAGE AREA :

If you want to keep track programmatically of when the storage area changes, you can trap the storage event. The storage event is fired on the window object whenever setItem(), removeItem(), or clear() is called and actually changes something. For example, if you set an item to its existing value or call clear() when there are no named keys, the storage event will not fire, because nothing actually changed in the storage area.

HTML5 STORAGE IN ACTION

Recall the Halma game we constructed in the canvas chapter. There’s a small problem with the game: if you close the browser window mid-game, you’ll lose your progress. But with HTML5 Storage, we can save the progress locally, within the browser itself. Here is a live demonstration. Make a few moves, then close the browser tab, then re-open it. If your browser supports HTML5 Storage, the demonstration page should magically remember your exact position within the game, including the number of moves you’ve made, the position of each of the pieces on the board, and even whether a particular piece is selected.

How does it work? Every time a change occurs within the game, we call this function:

function saveGameState() { if (!supportsLocalStorage()) { return false; } localStorage[“halma.game.in.progress”] = gGameInProgress; for (var i = 0; i < kNumPieces; i++) { localStorage[“halma.piece.” + i + “.row”] = gPieces[i].row; localStorage[“halma.piece.” + i + “.column”] = gPieces[i].column; } localStorage[“halma.selectedpiece”] = gSelectedPieceIndex; localStorage[“halma.selectedpiecehasmoved”] = gSelectedPieceHasMoved; localStorage[“halma.movecount”] = gMoveCount; return true; }